Yeah -- like now ?

Patch face veneer invisibly ? You know better than that !

As I've reported before, I was able to make an invisible repair to a newly-made rift-oak veneered drawer front -- because we still had scrap from the same sheet of material. A pair of attachement-screw bores had mistakenly been made in the face (instead of the back) by "the kid." After securing the matching material I ploughed a pair of dadoes 1/8" deep and 1/2" wide from top to bottom, prepared a pair of inlay strips, and glued them in using a flat caul of prefinished material. After sanding, presto.

But these chair parts are not able to be so simply repaired: they are wavy structural pieces. Even a narrow single-ply removal, if it could be ploughed somehow, would potentially weaken the part. And acquiring perfectly-matched veneer is literally out of the question -- as you can imagine.

So, the remedy is to remove all finish, patch the holes, making the surface perfectly sound and fair, and then applying a new veneer. This could be done with a vacuum bag; the veneer could be treated to a marinade of glycerine-and-water mix to soften it as an aid to conforming to the irregular surface shape.

Yes, that would be a fall-back choice, I suppose. The value of the chair, both aesthetic and monetary, suffers correspondingly, wouldn't you say ?

Maybe the OP should be referred to the new "Cushions: form vs function" thread . . . !

There's always Contact Paper, in an attractive woodgrain or maybe a daisy pattern.

Readers having difficulty understanding my comments about patching veneer might not recognize the underlying issue: it is that side-to-side matches are often perfectly hidden, while those where a cut across the grain is met with another piece of wood -- even from the same board -- are impossible to disguise. A look at any wood floor will illustrate the point. Wood is unusual among materials because of this directionality.

The same problem exists when joining two pieces of wood with glue, curiously: pieces glued side to side can make a perfectly strong joint, while pieces glued end to end must be reinforced with some mechanical joinery.

So this explains why my drawer-front repair involved making a full cut, from edge to edge of the workpiece, and replacing that stripe with a fully-matching insert. And only because the wood was rift-sawn -- which gives the appearance of parallel narrow lines of grain -- was the repair able to disappear.

Yes, perhaps the best "remedy" is to make a neat and honest plug or patch -- preferably of a regular and repeated shape, such as a disc -- and let the chair be what it is ?

Not seeing the extent of the repair required for your DCW, I had seen examples that have a very small faux wood grain done as a temporary resort (it should be reversible whatever repair you do on anything) but it requires a great amount of skill. If you can say you can paint like Jan Vermeer, this might be an option for you. Faux wood graining or faux bois technique dates back to the 1700's.

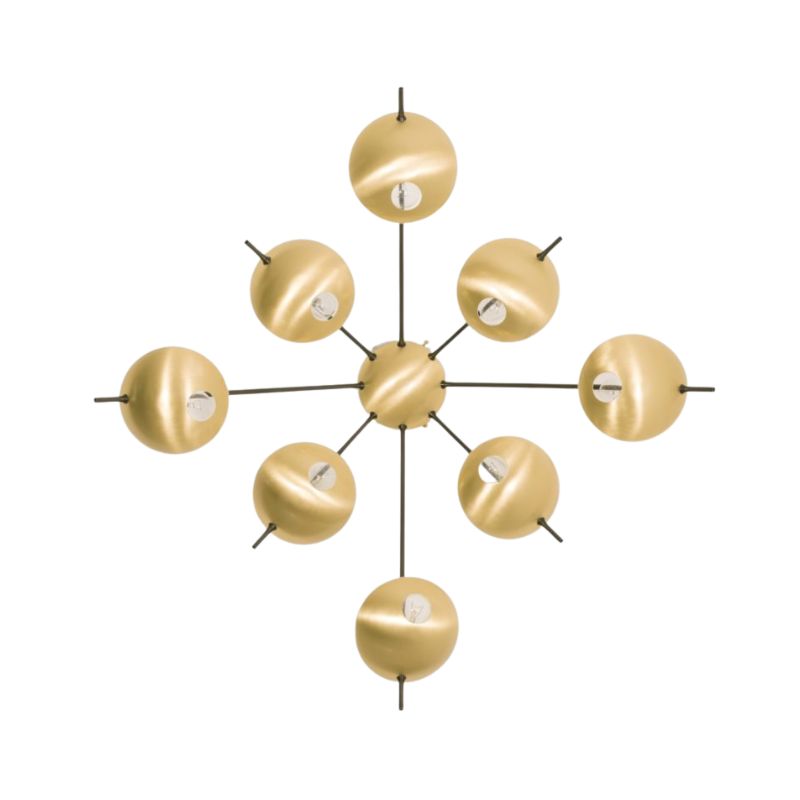

If the you have piece is in poor to very poor condition and no longer has any value even with a decent repair, some DCW have a black matte lacquer finish on them or if you are adventurous and have some remnants of slunkskin or cowhide floating around...maybe?

or at least try to get as close as the current production finishes/options.

http://www.hermanmiller.com/content/dam/hermanmiller/documents/materials/reference_info/Product_Chip_Chart_Eames_Molded_Plywood_Chairs.pdf

This might be off topic showing another Eames chair repair by the masters themselves Charles and Ray Eames on one of their vinyl clad fiberglass chair.

http://www.eamesoffice.com/blog/how-to-re-upholster-an-eames-fiberglass-chair/

If you need any help, please contact us at – info@designaddict.com